David T. Rubin, MD: Undaunted in his quest to improve the lives of patients with inflammatory bowel disease and other digestive ailments

Provided by UChicago Medicine

Patients come through his door looking for answers and relief. The symptoms that began as a nuisance have turned painful and chronic. Their bodies have turned on them.

David T. Rubin, MD, is a world-renowned expert on the treatment and research of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. He’s a tireless educator — in classrooms, at conferences and on Twitter, where he’s known as @IBDMD — and an ardent advocate for people living with IBD. His preeminence was recognized in 2020 with the Sherman Prize, one of the most prestigious awards in his field. Becker’s Healthcare recently named him to its list of “10 GI Leaders to Know.”

“David is in a very elite category,” said Miguel Regueiro, MD, Chair of the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition at the Cleveland Clinic, who has known Rubin for decades. “He’s doing cutting-edge clinical research and is really one of the leaders of education in the field of IBD internationally.”

Rubin is the type of doctor who becomes lifelong friends with his patients. He’s been known to help edit a paper of a patient who has gone off to college — you’re never a former patient of Dr. Rubin’s — and receives gifts like custom-made coffee mugs proclaiming “Colon Whisperer.”

For his new patients, he is the confident, optimistic, reassuring voice they need to hear.

“The first thing I tell my patients, especially those who have been newly diagnosed, is that we’re going to treat it early, and we’re going to treat it hard, because after we do that I would like you to be in remission for the rest of your life,” said Rubin, Section Chief of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at the University of Chicago Medicine.

The problem, as Rubin knows as well as anyone in the world, is that it is rarely that easy. Rubin explains to his patients that while recent advances provide doctors and patients with the tools to manage these diseases, none is perfect, and there are no cures.

But he is also sure his patients hear one final thought: This disease will not ruin your life. It does not define you.

These are particularly comforting and important ideas to hear because Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis typically first develop in teens and young adults between the ages of 15 and 30.

Which likely explains another coffee mug he received as a gift: “Keep calm and call Dr. Rubin.”

Understanding IBD

As many as 70,000 Americans will be diagnosed with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis next year, joining more than 3 million others in the U.S. who live with these chronic conditions. Just as with other immune-mediated diseases, they are becoming more common.

Globally, as many as 10 million people live with IBD, with the highest incidence in Europe and North America. But since 1990, the incidence in more recently industrialized nations in Asia, Africa, and South America also has been rising rapidly.

To understand IBD, it is necessary to explore one of the most underappreciated parts of the human body. The digestive system is nothing short of a marvel. Comprising the gastrointestinal tract the hollow organs forming a tunnel through your body — plus the liver, pancreas and gallbladder, it harvests the nutrients from everything you eat and drink, breaking them down to be absorbed through the cells lining the system, and then packages the waste for subsequent elimination.

Inflammatory bowel disease and the microbiome

But scientists now know that the system does so much more. There’s a growing appreciation that a key player in human health is the microbiome — the collection of microbes, be they bacteria, fungi, protozoa, or viruses — that lives in and on the human body, with the largest concentration in the gut. Microbes outnumber human cells 10 to one. By one estimate, a person’s microbiome weighs as much as 5 pounds — yet it wasn’t generally recognized to exist until the late 1990s.

The microbiome is essential for such wide-ranging tasks as brain development, nutrition and fighting infection.

It’s no wonder we admire people with guts.

Scientists tell us the microbiome also plays a role in obesity, food allergies and in diseases such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and, of course, inflammatory bowel disease.

“When you have a healthy immune system in your intestines, it continuously responds to the environment,” Rubin says, explaining that that the gut is exposed to the environment more than any other part of the body except the skin. “So, every time you eat, you’re exposing your intestines to what’s coming from the outside world.”

In normal situations, this sophisticated system becomes mildly inflamed after a meal and then shuts itself off and goes back to a resting state, distinguishing between nutrition and pathogens.

“What happens with IBD is that the inflammatory system of the gut is turned on but doesn’t turn itself off, either because the patient has lost their “off switch” or because there is ongoing stimulation by something we are yet to discover,” Rubin said. “Either way, when the inflammation continues, it causes damage.”

Symptoms can be extremely uncomfortable and vary based on the location of the inflammation. Patients can experience pain and cramping, more frequent bowel movements, diarrhea and bleeding.

“Patients usually end up losing weight because they learn consciously or subconsciously that when they eat less, they have fewer symptoms,” Rubin said.

Crohn’s disease can involve any part of the GI tract from the mouth to the anus, while ulcerative colitis attacks only the large intestine. In addition, Crohn’s can be patchy, appearing in one place but not another; ulcerative colitis is continuous in its distribution.

“Treatments are aimed at turning off the inflammation,” Rubin said. “And we’ve made great progress in managing these conditions. When I started my training, we basically had no treatments. Now there are more than 15 available, effective and safe treatments.

Biological therapies for inflammatory bowel disease

That includes the revolutionary development of biological therapies for IBD. Biological therapies are proteins that are made in living cells. There are now three classes of biological therapies available for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

The first class, the anti-TNF class, includes drugs that block the body’s signals that fight infection or cause inflammation. By targeting the inflammatory protein called TNF, anti-TNF therapies can shut down inflammation broadly across the body. These drugs are also used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and other inflammatory conditions.

Another biological antibody therapy selectively targets the white blood cells on their way to the bowel. The newest antibody class targets a different inflammatory protein called IL-23, and works in IBD and psoriasis.

“The strategy is to turn down the overactive immune response long enough so that the body can take over and then heal,” Rubin explained.

The latest treatment for inflammatory bowel disease

The newest treatment focus is on synthetic targeted small molecules, which work on specific enzymes or other mechanisms of inflammation. These molecules are small enough to be delivered as pills and be absorbed into the bloodstream.

Finally, 5-ASA therapies, which Rubin has been studying for years, were first developed in the early 1950s to treat arthritis. These therapies don’t suppress the immune response, but are believed to affect the immune activity in the lining of the bowel.

With so many options, it would seem that patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis can live worry-free, even if a cure isn’t found. But then the human body proves again why it is such a marvelous example of biological engineering.

“Remember that we’re not treating the cause of IBD, we’re treating the result of it,” Rubin said. “The immune system of the gut is there to protect us. It still thinks there is a threat. So, it can be just a matter of time before it finds a new pathway and the inflammation returns.”

As a clinician-scientist, Rubin attacks these problems from all angles, pushing our understanding of biology and disease in his research while analyzing and assessing the stream of information coming from his patients. Each patient’s unique biology might provide a special insight into how IBD works.

“So these are the things — I’m not making this up — they literally keep me awake at night,” said Rubin. “Is this the patient who is going to be the key to what we’re trying to find?”

There’s one more complication. Rubin and his colleagues across IBD research and treatment may be dealing with multiple diseases.

“It might be because what we call Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are more like 50 different diseases that all look similar, but the body can only express itself in certain ways,” Rubin said.

Microbiome research

Eugene Chang, MD, is the director of the Microbiome Medicine Project, a collaboration between the University of Chicago, Argonne National Laboratory and the Marine Biology Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass. Chang founded the program in 2017 to promote cross-disciplinary research in the microbiome and support translational and clinical investigators studying a multitude of disorders, but his interest in the subject dates back to the turn of the millennium. Chang’s lab was well positioned then to be among the first groups to receive grants from the National Institutes of Health’s Human Microbiome Project.

Chang, a frequent collaborator with Rubin, studies how the gut microbiome affects IBD. He considers the microbiome to be like another organ of the body, though one that is acquired early in life instead of inherited.

“The human microbiome has changed rapidly in just the past hundred years,” Chang said. “It is influenced by diet, lifestyle and xenobiotics, like antibiotics, that are so common now. So our microbiome is much less diverse. There are certain microbes that have disappeared in many populations. It is a real disturbance in the normal evolutionary pressures that would determine which microbes we match to our own needs, for example, in immune or metabolic systems.”

Chang said the consequences have not been good, creating a mismatch between us and our microbes. “I think that underpins the increase in these new age disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease, but also other autoimmune and inflammatory disorders, such as asthma or rheumatoid arthritis,” he said. “But we’re still just scratching the surface of the science.”

Chang said he first met Rubin because they had the same mentor, Joseph B. Kirsner, MD, PhD, who is considered the grandfather of modern IBD research and treatment and put the University of Chicago on the map as an IBD pioneer.

“I remember Kirsner saying, ‘You need to meet this really bright, superstar medical student,’” Chang said, though he didn’t really get to know Rubin until he joined the faculty.

Chang said Rubin’s many talents make him a “quadruple threat.”

“He’s an outstanding clinician, a wonderful educator — my gosh, you should listen to him give a talk — and an outstanding clinical investigator,” he said. “And finally, I think he is a superb section chief. He has vision, he gets things done, and knows how to select the right people for key tasks.

“David is really a remarkable individual.”

Game-changing care

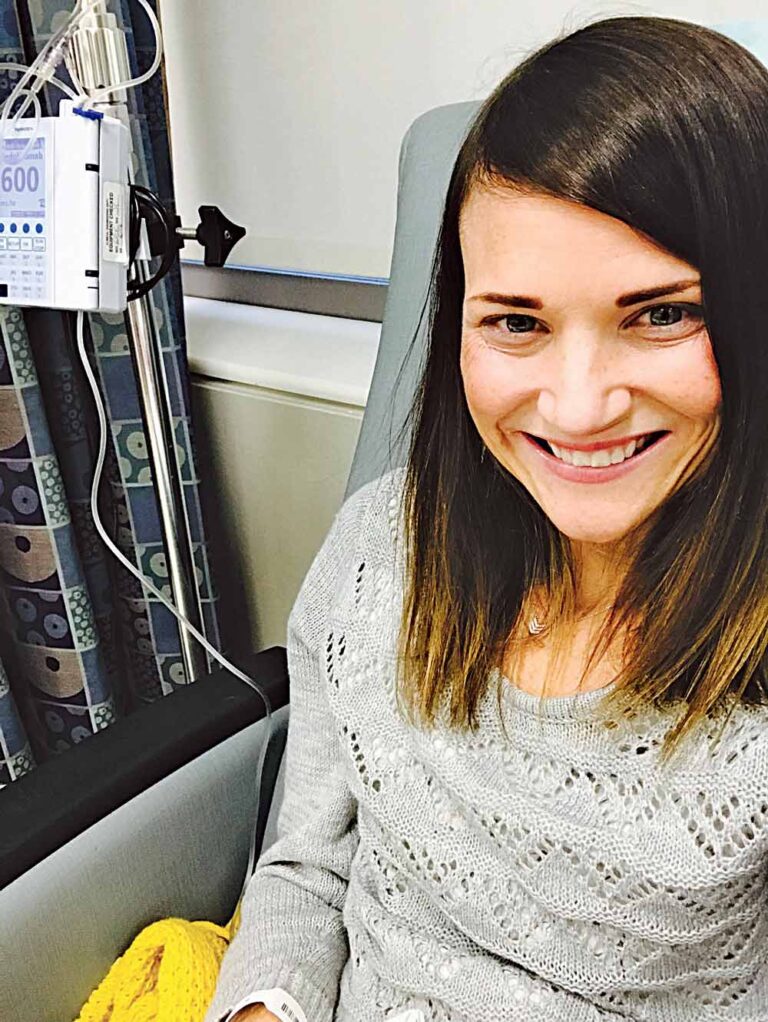

Rachel Hendee’s story captures the recent history of IBD treatment in a nutshell. Diagnosed with severe Crohn’s disease at age 14 in the mid-1990s, she had surgery to remove part of her small and large intestines just a year later at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Hospital. Her ongoing care was still through a specialist in her hometown of Freeport, Ill., about 115 miles northwest of Chicago, but he began sending her to UChicago Medicine for regular checkups to monitor her condition.

“During those first five or six years, I did OK, but the disease always came back,” Hendee said. “This was before there were very many options so I went through all those available at the time.”

In the late 1990s, Remicade (the first anti-TNF therapy) was approved, and Hendee said she was the first in Freeport to receive it.

“Remicade was a miracle drug,” she said. “I had never felt so good in years.” The medication meant Hendee was able to go away to college to earn an undergraduate degree. It even meant she could go to China for a year to teach English.

But her health declined precipitously when she returned. She started cycling through drug protocols that would only work for short periods, and underwent 10 surgeries and countless smaller procedures. Despite her difficult health situation, she still managed to return to school and earn a degree as a physician assistant. About seven years ago, she transferred her care full time to UChicago Medicine and became Rubin’s patient.

“That was a game changer,” Hendee said. She appreciated how he approached her care, how he was willing to try new medications and had the reputation, expertise and Twitter platform to successfully appeal to her insurance company to pay for it. Finally, though, in 2019, when her body fought off another round of medications, she and Rubin decided the best course of action was to have her colon removed.

“I’ve probably felt the best I have in the 25 years since I was diagnosed,” she said. “The sad irony was that I had surgery at the end of December and in March was feeling better and finally wanted to go out and be social and the pandemic hit.”

Hendee, now a physician assistant in colon and rectal surgery at another Chicago hospital, says her early diagnosis and experience played a big role in her career decision. It maybe isn’t so surprising that she often sounds like her doctor and mentor.

“One of the most important things newly diagnosed patients need to know is that it will get better and that they will be able to enjoy a long life,” she said, adding that it helps when they see her in her white coat and hear it from her. Hendee said her own expertise in the field has only increased her admiration for Rubin. When she learned about the Sherman Prize, she decided to nominate him for the award.

“Dr. Rubin is really amazing,” she said. “I think that quite possibly he is the busiest person I know, but when you’re in that appointment with him, you feel like you’re his only patient.”

David T. Rubin, MD

Joseph B Kirsner Professor In Medicine

Chief, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition

Dr. Rubin specializes in the treatment of digestive diseases. His expertise includes inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) and high-risk cancer syndromes.

For more information, visit www.uchicagomedicine.org/global