‘Beyond Everyday’: Specialist Infusion Management

Ece Aydinc. RN. Becton Dickinson. Clinical Resource Consultant, Medication Management Solutions, Turkey.

Samuel Garcia. RN, BHSc. Becton Dickinson. Medical Affairs Director, Medication Management Solutions, Europe, Middle East and Africa..

James Waterson. RN, MMedEd. MHEc. Becton Dickinson. Senior Medical Affairs Manager, Medication Management Solutions, Middle East & Africa.

Tina Worth. HV, RGN, LLM, MBA. Becton Dickinson. Senior Medical Affairs Manager, Medication Management Solutions, Europe, Middle East and Africa.

As Medical Affairs and Clinical Professionals working in the field of infusion and medication safety, we are often asked about some of the more specialist uses of infusion therapy and infusion pumps. Not every IV-therapy is a simple maintenance infusion of Normal Saline!

Subcutaneous Infusion

Subcutaneous infusion administration has been around as a therapy for a very long period of time, but it has attracted a great deal more interest recently.

Continuous Subcutaneous Infusion (CSCI) delivered by syringe pump is a useful administration method in pain management.1 There is evidence that drug therapy with continuous subcutaneous infusions (CSCI) over 24 to 48 hours has several benefits, both in patient care and in the application of healthcare resources.2

Beyond this, the scope for CSCI to

deliver other medications, therapies, and intravenous fluids for hydration has expanded to manage situations such as venous depletion, and practice recommendations for subcutaneous infusions of fluids and medications have been developed.3 Among the recommendations for Assessment, Best Practice, and Competency are:

- Assess the intended duration of therapy, reasons for using the parenteral route, the properties of the solution/medication, and the patient’s clinical, tissue, and skin condition.

- Complete an interprofessional team hydration/nutrition/electrolyte assessment to determine the patient’s fluid and electrolyte needs.

- Review the medication product monograph to determine suitability.

- Ensure that subcutaneous medications and hydration prescribed are at rates, frequency, and volumes/dosage appropriate for the patient’s age, weight, clinical condition, individual subcutaneous absorption, laboratory values, and as recommended by the drug manufacturers or supporting literature, and generally not exceeding those used for IV infusions.

- Avoid infusion rates >5 mL/h for medications (unless recommended by manufacturer, eg, subcutaneous immunoglobulin). Slow infusion rates and use of diluted solutions have been recommended in the literature for subcutaneous antibiotics.

- Select a site for subcutaneous access with intact skin and adequate subcutaneous tissue (eg, minimum 1.0-2.5 cm thickness).

- Consider use of 2 or more sites as required for high-volume solutions.

Subcutaneous infusion offers several advantages over intravenous infusion, including ease of application, lower costs, and a lack of potential serious complications, particularly infections. Subcutaneous infusion may be of particular value in patients with mild to moderate dehydration or malnutrition.4

Regional Analgesia or ‘Nerve Block’ Infusions

In terms of delivering analgesia to meet acute pain needs both peri-operatively and post-surgery, Regional Nerve Block infusion analgesia delivered via smart analgesia pumps is beginning to show significant advantages over general anesthesia and traditional peri-operative and post-operative analgesia regimes.

In one recent study patients undergoing upper limb surgeries showed significantly higher satisfaction scores than those who received general anesthesia5 and the technique has been preferred at other centres for lower limb surgery as it has lower operating room duration per case than general anesthesia6 with results comparable to general anesthesia for pain control.

In terms of patient safety, the technique can be useful for patients who might be considered to be high risk for respiratory depression with parental analgesia.

The Faculty of Pain Medicine of the United Kingdom recommends the use of grey tubing to differentiate regional infusions from other infusion routes.7

Epidural Infusions:

To reduce the risk of incorrect connections and injections the ISO 80369 series of standards was issued in 2016. It defines a separate, incompatible connection for epidural and regional block anesthesia and analgesia.

In simple terms, an intravenous administration line or standard syringe will not fit an NRFit® epidural cannula, and an NRFit® epidural administration set will not fit onto an intravenous cannula.

Epidural administration line safety goes beyond the connector, however. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) state that facilities should always, ‘use yellow-lined tubing without injection ports for epidural infusions to set its appearance apart from typical IV tubing, and never use yellow-lined tubing for anything other than epidural administration.’8

The Faculty of Pain Medicine of the United Kingdom in its ‘Best Practice in the Management of Epidural Analgesia in the Hospital Setting’ recommends the use of yellow tubing to differentiate epidural/spinal lines from arterial (red), enteral (purple) and regional (grey) infusions.7

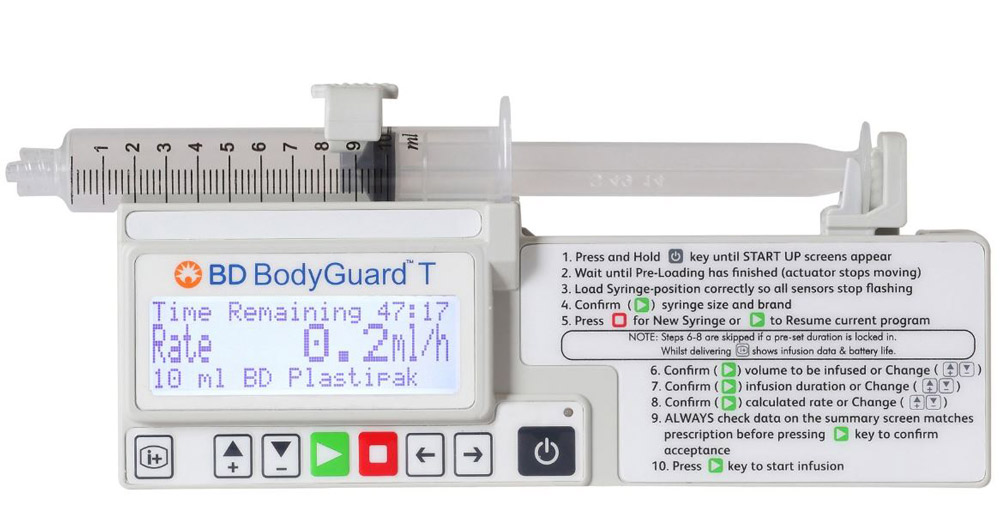

It is usual for facilities to set pre-programmed epidural therapy protocols for maternity units and for surgical units. Each protocol would specify background rate, lockout time and patient bolus, clinician bolus and PIEB (Programmed Intermittent Epidural Bolus). The protocols are commonly set as total dose per hour, and can be set as weight-based, by dose/kg.

Extra boluses may be delivered at the clinician’s discretion, with soft and hard dose limits applied to these doses and to the background rate, patient doses, and any PIEB settings.

In PIEB the pump delivers an intermittent dose of analgesia on a set cycle, whilst maintaining the background infusion and allowing patient boluses which are regulated by a lockout period. There have been some studies that indicate shorter duration of maternal labor and improved patient satisfaction with PIEB.9

The theory behind PIEB is that the automated bolus improves the spread of anesthetic solution within the epidural space, and therefore enhances the sensory blockade.10

Arterial Line, Pulmonary Artery, and Right Atrial Line Maintenance, and Flush Options

In many adult intensive care units pressurized flush bags are used to deliver approximately 3ml/hr of flush of normal saline per catheter to maintain the patency of arterial lines and central venous catheters. These bags require attention to maintain the pressure bag at the required 300 mm Hg of pressure.11, deviation from this setting may affect flow. Using IV syringe pumps to deliver these specialist catheter maintenance infusions will give a documented accuracy for the volumes delivered and may require fewer nursing interventions to maintain flush patency. The use of syringe drivers at rates of 0.5-1 ml/hr to maintain specialist line patency has been a common practice in neonatal and pediatric critical care for a considerable period of time.

Flushing of the catheter after blood sampling can be achieved with pre-set hands-free boluses delivered via the pump and from within the medication library. Flush solutions can also be added to barcode medication administration (BCMA) libraries and order strings to help ensure ‘right patient- right medication’ processes are maintained.

There have been reported ‘wrong medication’ instances of inappropriate fluids such as glucose being inadvertently administered via arterial lines.12 BCMA could help to substantially reduce this risk.

Multistep Infusion Administration

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is a biological agent used to manage autoimmune, infectious, and inflammatory conditions. Patients receiving initial (first-time) IVIG infusions and high-risk patients should be monitored carefully for any infusion-related reactions or adverse effects.

Generally, the infusion rate commences at a rate of 0.5 to 1 mL/kg/hour for the first 15 to 30 minutes, and if no adverse reaction occurs, then the rate can be increased subsequently every 15 to 30 minutes to a maximum of 3 to 6 ml/kg/hour, though this regimen is also dependent on the individual medication manufacturer’s instructions for use.13 This process can be very labor-intensive and adds to the nursing workload- the nurse must check the patient’s condition at each interval before allowing the rate to be increased.

Multistep infusions undertake the necessary rate change automatically at pre-programmed intervals, this can release the nurse from programming each step and allow them to concentrate on the patient’s condition, vital signs, and comfort.

‘Ramping’

The optimal blood glucose target for patients in the intensive care unit has not been definitively defined, but a target of 140 to 180 mg/dL (7.8-10 mmol/L) has been accepted by most critical care societies worldwide.14

‘Stress hyperglycemia’ in the critically ill patient can be caused by excessive counterregulatory hormones such as corticosteroid, glucagon, growth hormone, and catecholamines, and the release of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and interleukin (IL)-1.

These factors can promote transient insulin resistance that can lead to decreased insulin action on suppressing gluconeogenesis and also to decreased uptake of insulin-mediated skeletal muscle glucose.15

Hyperglycemia is also aggravated by medications such as steroids and catecholamines, parenteral nutrition, and intravenous medications diluted in dextrose.16

This insulin resistance can be particularly important during the beginning and ending of infusions of total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) as the glucose load of the infusion can be expected to raise the blood glucose level, but the insulin response to normalize the blood glucose is inhibited. The ramping effect in TPN programs available in some infusion pumps can give time for the physiological response to ‘catch up’ with a more slowly rising glucose load.

Furthermore, these programs can also ‘ramp down’ to allow the blood glucose to fall in a more controlled fashion at the end of the TPN infusion and to give more time for physiological mediators to achieve normoglycemia.

Radioactive Isotope Intravenous Administration

Lutetium-177 (Lu-177) is a medical isotope used in targeted radionuclide therapy for treating neuroendocrine tumors and prostate cancer. It is currently the most commonly used isotope for targeted radionuclide therapy.

It can be intravenously administered and one set of authors noted that whilst, ‘the gravity infusion method is cost-effective, we identified some challenges that increased the possibility for error, contamination, and excessive radiation exposure.’17

Use of an infusion pump and protocol was found to ‘reduce error, the possibility of contamination, and most importantly radiation exposure.’ Lu-177 has a radioactive half-life of 6.5 Days 18 so if the frequency of use of Lu-177 treatments is more frequent than this then it is practical to treat the intravenous pump as effectively always at risk of radioactive contamination. General management should include the use of one infusion pump dedicated solely for Lu-177 administration, with the pump clearly labelled as a Lu-177 pump.

In the case of wireless networking, it can be of value to either disable the wireless on this pump and limit the medication library on the pump to Lu-177 only or to create a single pump network configuration only for pumps used with isotopes. Users can build a local library for the Lu-177 pump with duration and volume / dose as this can make programming set-up time shorter (with less risk of exposure for staff) but ml/hr program may be used if this is found to be simpler and quicker. Each infusion administration set should be disposed of as per local policy for radioactive disposables.

Administration of Blood Stem Cell Products

Previously cryopreserved, peripheral blood stem cell products are administered intravenously. The administration should be rapid (less than 30 minutes per unit) to reduce cellular damage caused by dimethyl sulfoxide exposure after thawing.19 Cells are typically thawed at the bedside and infused by gravity through a high-flow rate central venous catheter. It has been common practice to infuse the cells either by gravity or via a manual syringe push. A 2018 study raised concerns over these practices as the time for infusion can vary substantially with the gravity infusion method, and transfer of the stem cell product to a syringe potentially increases the risk of product contamination. Manual syringe pushes also increase the risk of excess variation in vein pressure during administration.19

The 2018 study compared the use of a volumetric pump to the use of gravity. The research team found that the infusion pump delivered more consistently within the prescribed time of administration, with 20% of the products infused by gravity having incorrect infusion rates of less than 2.5 mL/min, compared with only 5% for products infused by infusion pump. During the study, unusually slow infusion rates for two transfusions via gravity required the transfer of the product to a syringe at the patient’s bedside.

The infusion pump provided a controlled infusion for both small and large volume transfusions, without the need for transfer to syringes.

Infusion of stem cells is most commonly undertaken under the direction of a physician and rates may be adjusted according to the patient’s toleration of the therapy. This is more easily and accurately managed with an infusion pump than with gravity.

In the 2018 study, in the two groups of patients who received stem cells via pump and via gravity no significant differences were seen between the two methods for measured clinically important variables such as Trypan Blue and Total Nucleated Cells. The study’s authors concluded that infusion pumps can be used safely for thawed stem cell products, and that infusion by pump can provide a reliable and consistent infusion and eliminate the need to transfer products to syringes.19

Off-Label Warnings

Healthcare professionals are always looking for new and imaginative ways to improve care, increase efficiency, and improve workflows. However, BD infusion pumps, as medical devices, have defined uses laid out in their Instructions For Use. Any use of the device beyond these specific use cases requires discussion with the respective department of BD Medical Affairs. Please feel free to reach out via your local BD representative to contact your regional BD Medical Affairs Department.

References:

- Dickman A, Bickerstaff M, Jackson R, Schneider J, Mason S and Ellershaw J, Identification of drug combinations administered by continuous subcutaneous infusion that require analysis for compatibility and stability, Dickman et al. BMC Palliative Care. 2017.

- Baker J, Dickman A, Mason S, Bickerstaff R, McArdle A, Lawrence I, Stephenson F, Paton N, Kirk J, Waters B and Ellershaw J, An evaluation of continuous subcutaneous infusions across seven NHS acute hospitals: is there potential for 48-hour infusions? BMC Palliative Care. 2020.

- Broadhurst D, Cooke M, Sriram D, Barber L, Caccialanza R, Danielsen MB, Ebersold SL, Gorski L, Hirsch D, Lynch G, Neo SH, Roubaud-Baudron C, Gray B. International Consensus Recommendation Guidelines for Subcutaneous Infusions of Hydration and Medication in Adults: An e-Delphi Consensus Study. J Infus Nurs. 2023 Jul-Aug 01;46(4):199-209. doi: 10.1097/NAN.0000000000000511. PMID: 37406334; PMCID: PMC10306332.

- Caccialanza R, Constans T, Cotogni P, Zaloga GP, Pontes-Arruda A. Subcutaneous Infusion of Fluids for Hydration or Nutrition: A Review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2018 Feb;42(2):296-307. doi: 10.1177/0148607116676593. Epub 2017 Dec 20. PMID: 29443395.

- Suresh P, Mukherjee A. Patient satisfaction with regional anaesthesia and general anaesthesia in upper limb surgeries: An open label, cross-sectional, prospective, observational clinical comparative study. Indian J Anaesth. 2021 Mar;65(3):191-196. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_1121_20. Epub 2021 Mar 13. PMID: 33776108; PMCID: PMC7989486.

- Neal-Smith G, Hopley E, Gourbault L, Watts DT, Abrahams H, Wilson K, Athanassoglou V. General Versus Regional Anaesthesia for Lower Limb Arthroplasty and Associated Patient Satisfaction Levels: A Prospective Service Evaluation in the Oxford University Hospitals. Cureus. 2021 Aug 9;13(8):e17024. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17024. PMID: 34522505; PMCID: PMC8425506.

- https://fpm.ac.uk/sites/fpm/files/documents/2020-09/Epidural-AUG-2020-FINAL.pdf

- https://www.ismp.org/resources/epidural-iv-route-mix-ups-reducing-risk-deadly-errors

- George RB, Allen TK, Habib AS. Intermittent epidural bolus compared with continuous epidural infusions for labor analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2013 Jan;116(1):133-44. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182713b26. Epub 2012 Dec 7. Erratum in: Anesth Analg. 2013 Jun;116(6):1385. PMID: 23223119.

- Riley ET, Carvalho B. Programmed Intermittent Epidural Boluses (PIEB) for Maintenance of Labor Analgesia: A Superior Technique to Continuous Epidural Infusion? Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2017 Apr;45(2):65-66. doi: 10.5152/TJAR.2017.09031. Epub 2017 Apr 1. PMID: 28439433; PMCID: PMC5396898.

- McGee, W, Young, C., Frazier, J. (Eds.). (2018). Edwards clinical education: Quick guide to cardiopulmonary care (4th ed.). Retrieved September 9, 2022, from https://education.edwards.com/quick-guide-to-cardiopulmonary-care-4th-edition/220356#

- https://www.baccn.org/static/uploads/resources/HSIB_The_use_of_an_appropriate_flush_fluid_with_arterial_lines_Report.pdf

- Kareva L, Mironska K, Stavric K, Hasani A. Adverse Reactions to Intravenous Immunoglobulins – Our Experience. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018 Dec 20;6(12):2359-2362.

- Alhatemi G, Aldiwani H, Alhatemi R, Hussein M, Mahdai S, Seyoum B. Glycemic control in the critically ill: Less is more. Cleve Clin J Med. 2022 Apr 1;89(4):191-199. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.89a.20171. PMID: 35365557. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.89a.20171

- Corathers SD, Falciglia M. The role of hyperglycemia in acute illness: supporting evidence and its limitations. Nutrition 2011; 27(3): 276–281. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2010.07.013

- McCowen KC, Malhotra A, Bistrian BR. Stress-induced hyperglycemia. Crit Care Clin 2001; 17(1):107–124. doi:10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70154-8

- Davis A, Pietryka M, Passalaqua S. Technical Aspects and Administration Methods of 177Lu-DOTATATE for Nuclear Medicine Technologists. J Nucl Med Technol. 2019 Dec;47(4):288-291. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.118.221846. Epub 2019 Apr 24. PMID: 31019033.

- Nuclide Safety Data Sheet: Lutetium-177 www.nchps.org

- Reich-Slotky R, Cushing M, Hsu Y, Ancharski M, Rojas J, Scrimenti L, Robilio S, Assalone D, Roselli T, Guarneri D, Vasovic L, Goel R, Shore T, van Besien K. Validating and implementing the use of an infusion pump for the administration of thawed hematopoietic progenitor cells-a single-institution experience. Transfusion. 2018 Feb;58(2):339-344. doi: 10.1111/trf.14409. Epub 2017 Nov 29. PMID: 29193156.